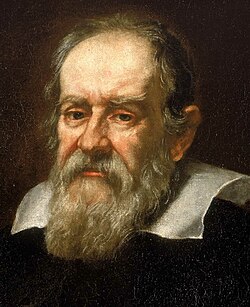

Galileo Galilei

The Italian mathematician, astronomer, and physicist Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) was a supporter of Copernicanism who made numerous astronomical discoveries, carried out empirical experiments and improved the telescope. As a mathematician, Galileo's role in the university culture of his era was subordinated to the three major topics of study: law, medicine, and theology (which was closely allied to philosophy). Galileo, however, felt that the descriptive content of the technical disciplines warranted philosophical interest, particularly because mathematical analysis of astronomical observations – notably, Copernicus's analysis of the relative motions of the Sun, Earth, Moon, and planets – indicated that philosophers' statements about the nature of the universe could be shown to be in error. Galileo also performed mechanical experiments, insisting that motion itself – regardless of whether it was produced "naturally" or "artificially" (i.e. deliberately) – had universally consistent characteristics that could be described mathematically.

Galileo's early studies at the University of Pisa were in medicine, but he was soon drawn to mathematics and physics. At age 19, he discovered (and, subsequently, verified) the isochronal nature of the pendulum when, using his pulse, he timed the oscillations of a swinging lamp in Pisa's cathedral and found that it remained the same for each swing regardless of the swing's amplitude. He soon became known through his invention of a hydrostatic balance and for his treatise on the center of gravity of solid bodies. While teaching at the University of Pisa (1589–1592), he initiated his experiments concerning the laws of bodies in motion that brought results so contradictory to the accepted teachings of Aristotle that strong antagonism was aroused. He found that bodies do not fall with velocities proportional to their weights. The story in which Galileo is said to have dropped weights from the Leaning Tower of Pisa is apocryphal, but he did find that the path of a projectile is a parabola and is credited with conclusions that anticipated Newton's laws of motion (e.g. the notion of inertia). Among these is what is now called Galilean relativity, the first precisely formulated statement about properties of space and time outside three-dimensional geometry.[citation needed]

Galileo has been called the "father of modern observational astronomy",[32] the "father of modern physics", the "father of science",[33] and "the father of modern science".[34] According to Stephen Hawking, "Galileo, perhaps more than any other single person, was responsible for the birth of modern science."[35] As religious orthodoxy decreed a geocentric or Tychonic understanding of the Solar system, Galileo's support for heliocentrism provoked controversy and he was tried by the Inquisition. Found "vehemently suspect of heresy", he was forced to recant and spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

The contributions that Galileo made to observational astronomy include the telescopic confirmation of the phases of Venus; his discovery, in 1609, of Jupiter's four largest moons (subsequently given the collective name of the "Galilean moons"); and the observation and analysis of sunspots. Galileo also pursued applied science and technology, inventing, among other instruments, a military compass. His discovery of the Jovian moons was published in 1610, enabling him to obtain the position of mathematician and philosopher to the Medici court. As such, he was expected to engage in debates with philosophers in the Aristotelian tradition and received a large audience for his own publications such as the Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Concerning Two New Sciences (published abroad following his arrest for the publication of Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems) and The Assayer.[36][37] Galileo's interest in experimenting with and formulating mathematical descriptions of motion established experimentation as an integral part of natural philosophy. This tradition, combining with the non-mathematical emphasis on the collection of "experimental histories" by philosophical reformists such as William Gilbert and Francis Bacon, drew a significant following in the years leading to and following Galileo's death, including Evangelista Torricelli and the participants in the Accademia del Cimento in Italy; Marin Mersenne and Blaise Pascal in France; Christiaan Huygens in the Netherlands; and Robert Hooke and Robert Boyle in England.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий